Your Cart

- Title

- Copies

- Price

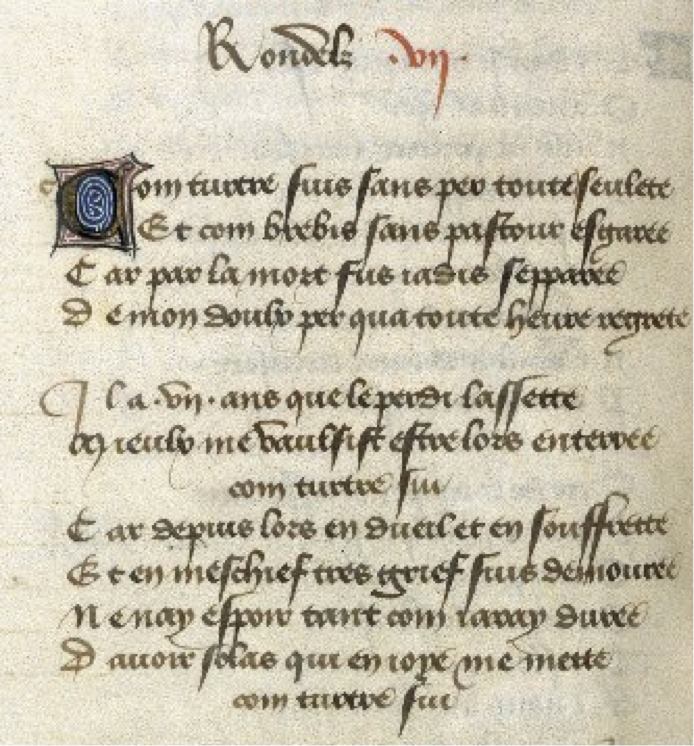

[ The first rondeau as it appears in British Library Harley MS 4431 (fol. 28v.), also known as The Queen's Manuscript and presented in 1414 by Christine de Pizan to Isabeau of Bavaria, queen consort of Charles VI. Christine is believed to have scribed some of the passages. ]

Like a turtle dovewithout her mateam I

— entirelyalone

Lambwithout shepherdwandering afield

Far fromdeathwho severed

My sweetest partall hoursspent longing —

Seven yearsweariedby losing

Better to bewith youburied

Like a turtle doveleft solitaryam I

Disarrayed by mourningleft

Wanting& in grief's meannessI abide

Never hoping —so long as I endure

To have solaceor a place of joy —

As a turtle dovewithout her mateamI

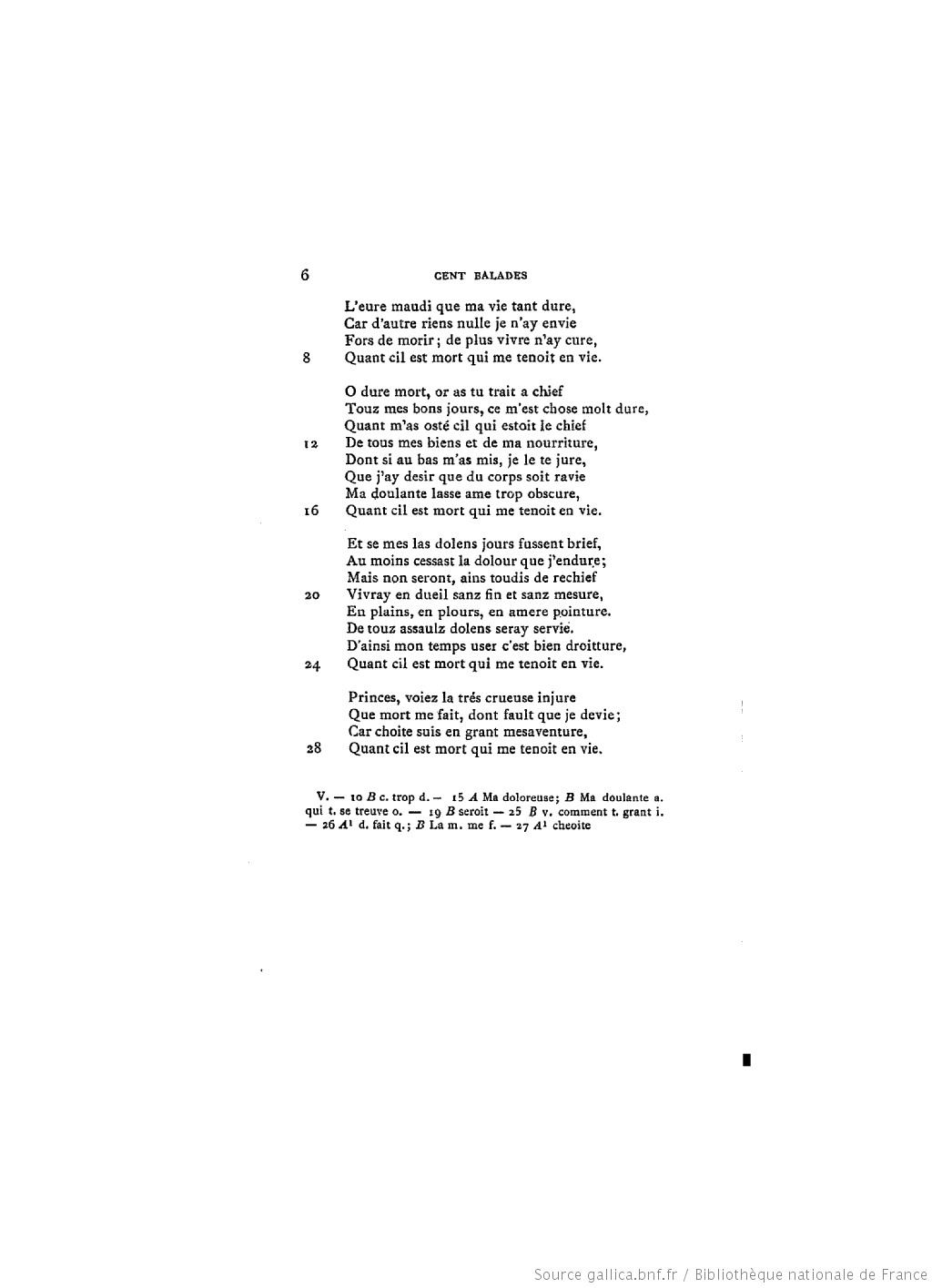

[ Oeuvres poétiques de Christine de Pisan. v. 1, published by Maurice Roy, 1886 BnF, p. 6. ]

[ Attack on Olivier de Clisson, Constable to King Charles VI and rumored to have disclosed a secret love affair of the Duke of Orléans. From the Harley Froissart. BL Harley 4379 fol. 152v. ]

Ardent burninghe bestowed mea generous purse

My lady

quench me

How could I not?

Six times myselfmy babes' mouths

hungryBy my soul —Rumor claims

He offeredMy ladyone thousandgold

crowns

tumbled&

From his handmy inkblackened

I flame

with desire —Enflamed my pen sent

Secret word to her

My ladycountrywomanfrombeyond

the clouded mountains : :

Duchess

newly wedlately wrongedBy my soul

My lady

Please —

In dreamshe hears the late king’sclocks sound

the hours& the church bells

Rouseherstricken limbs — Awake

before the sun

before her children

Riseshe lifts the latchsteals into

the dark mourning

after the last carousing

Heads toward the water’s edgeau bord du fleuve

dreams she mightslip in —

My mistressinfected by loss

prisoner of griefdeaf to God —

at the lobe of her earneither clock nor bells

norangel's whisper

but the aged tongueof the forever mortal sibyl

Gather nowthe shards

from your father’s treasure

Remember how

your beloveddid teach you this hand —

I vow I willnever forsake you

Wake nowdo not let the green river take you

but write instead

your vision —

The door to all our misfortunes was opened

& Iwho was still very

young entered —

The Book of Fortune's Transformation, 1403

he who knew well how to interpret the Pole Star & how to trim the sails

to keep a straight course

darkened sky cloud thick

crow's nest

disfigure my heart & face

corkscrew caught

whirlwind twistviolent into the sea

he who used to guide the shipnight & day through

all encumbrances & difficulties

I would have thrown myself as Alcyonelost Ceyx

held backmy heart ready

the very air trembledwith shoutsyells

bitter lamentationsdeep sufferings

hewho was such a good pilot

such a loyal loverthere would never be

anothersafe port

grief removed all fear my voice pierced the heavens

consolationdevastatedhopeless ofearthly solace

our desolated shipI could never again navigate

on that seaon the wrong sideof happiness

**

I have sincebeen on land

Fortune took pitybut her helpI do knot know

if it was more of a danger

wearied by long cryingI fell asleep early —

she palpated& took in her handseach bodily part

then departedour shipfollowing the waves of the sea

struck with great forceagainst a rock

I awakened& felt myselftransformed

limbs strongermyself bewildered

fleshstrengthenedmy voice much lowered& my

bodyharder & faster

Hymen's ring fallen from my finger —I found my heartstrong

& boldamazed at this strange adventure

I saw the sail & mast bad weather smashed

the ropes & the topsour ship brokenwater streaming

I set to repair with nails & pitch & strong hammering I

gathered mossamong the rocks& put

into holesuntil watertightI rejoined the broken edges

thus I became a true man (this is no fable)

Fortune taught me this trade

until deathI continue my life

extricated from the rocksmy ship

& set offtoward the placeI started out —

Il me semble qu'il a cent

Que mon ami de moy parti!

Il ara quinze jours par temps,

Il me semble qu'il a cent ans!

Ainsi m'a anuié le temps,

Car depuis lors qu'il departi

Il me semble qu'il a cent ans!

xxix

It seems to me a century

My love has from me parted

Fifteen days by time's measure

Each one seems a hundred years —

Such does my time grow late

Since the time

my love departed

It seems to me one hundred lives

Birdsongbells

the rooster calls&

the moonfoolish from carousing

her pathacross the night

slips into the earth

— • —

Before

the canopied route

a stand of trees

at attention

to sunlight

— • —

Morning grass

oceans the field

apple-sweet

ripening

vermillion

— • —

Swans liftoff the water

&their feathers

cloudthe sky

disappeared

in the rain-frothed river

— • —

Wind through the aspens

each day

a little of their greenflies away

uncovering

globesin the branches

readying

the forestfor sleep

— • —

Days turn

to years

each nightcloser

to her beloved

lit with starsshe can bear it

— • —

Where stone

bridges

the river

no time passesonly a boat

blueflat

over lily roots

— • —

As whenfrom a far distance

you see another&

whetherwalking towards

or away

you cannot tell

Cest anelet que j'ay ou doy

Mon doulz ami le m'a donné.

Souvent nous assemble toudoy

Cest anelet que j'ay ou doy.

Je l'aime bien, faire le doy;

Car pour ma joye est ordené

Cest anelet que j'ay ou doy.

liii

This ring around my finger

My sweetest love placed on me

Everlastingit joins us together

This ring encircling my finger

I love it well — this ring

My joyfulness sealed forever

By this ring circled round my finger

Your hands not on the table resting

but already on the page : inexplicable

yearning adorns us at once. However

else touch is apprehended, one can

listen for the scent of champignons, just

inside a tall oak door. A font of

snow quiets mountains, minerals tincture

saints leafed in gold. They garden shadows

lit by lemons. The sun does not always

announce her arrival, the painter does

not always leave a signature. Your hand

wrote me from a distant corner

how one can hear sixty voices enter a multitude

of cathedral arches. We do

sound every bell over ancient green

assemblages. Pray how we were never

parted, my hand folded always into yours.

Je vois

Jouer.

Au bois

Je vois.

Pour nois

Trouver

Je vois.

My voice

plays hide & seek

In the woods

I search

For us —

Finding

Music I sing

so that I would not grieve

too muchthe lossmy mistress

promisedshe wouldvisit

*

each timemusic plays

I hear her voicesinging

*

& when most desolate

to searchin the spoke of

Fortune's wheel

*

where music is housed

therecompose

the accompaniment

*

larkspurastersnapdragon

all the blueof her robe

woveninto chaplets

*

the windcircles

round usan enclave

of twoardent furious

groundwhirledto air

*

as the knight rides crusades

chainmailacross his chest

&by

his handa sword

*

syncopation

of dances

my mistressplays

*

music heard only

by a familyof daughters

*

she promisesmy voice

will return

one day —

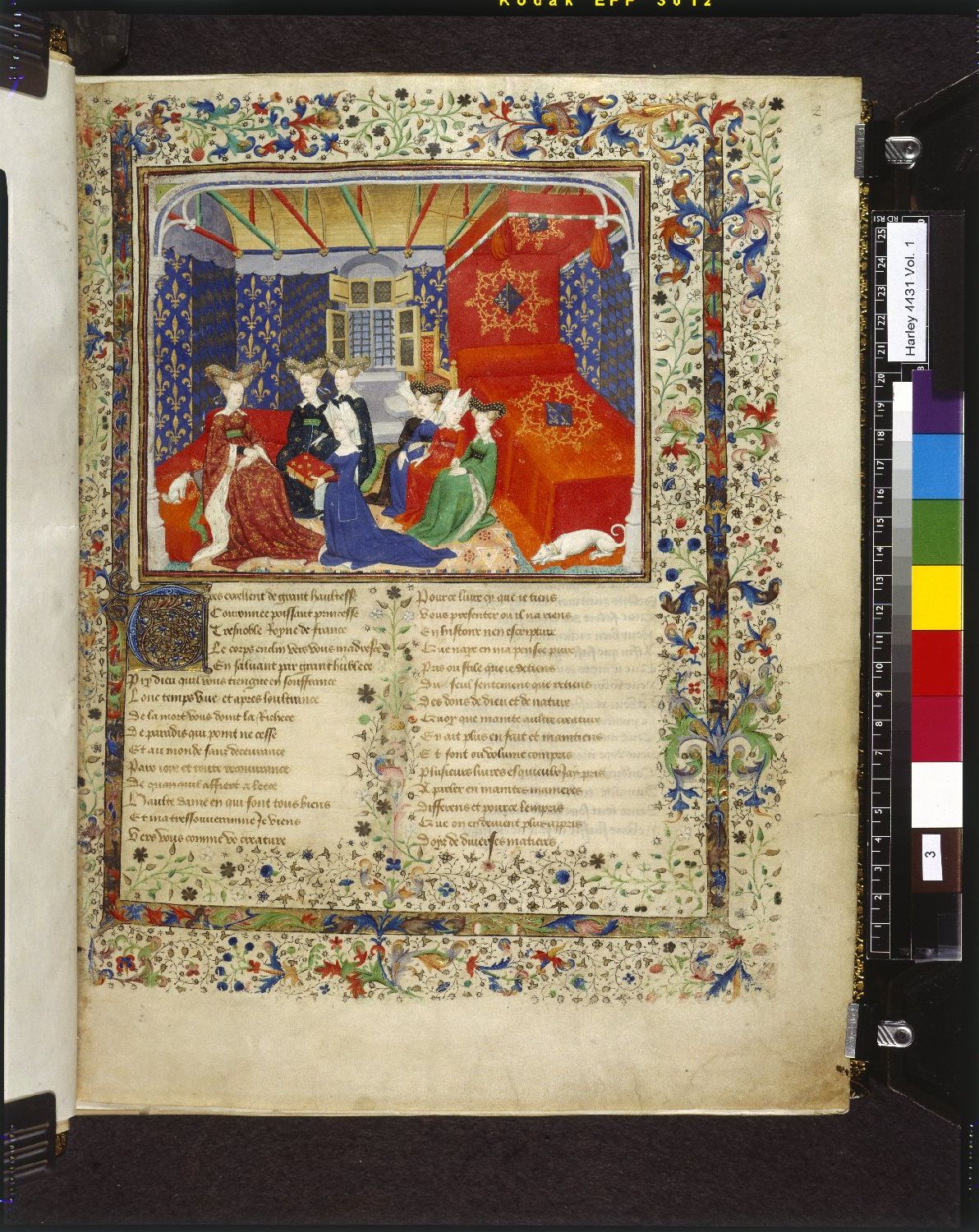

[ Christine presents her book to the Queen, BL Harley MS 4431, fol. 3r. ]

« Before the face, or eyes; A present, gift, offering; To all that have & shall be; to all alive & like to be; A presentation, a presenting, setting forth. »

~

Copied from Randle Cotgrave's

French-English Dictionary, 1611

on this day

of the 21st Century

by a scribe of

Christine

Christine de Pizan comes from elsewhere: first of all, from another language.1

Linguistic hospitality, therefore, is the act of inhabiting the word of the Other paralleled by the act of receiving the word of the Other into one's own home, one's own dwelling.2

1 ] Over six hundred years ago, a young foreign-born widow wrote about struggling to feed her kids, wearing a patched-up coat to do battle with creditors, fending off humiliating remarks and unwelcome sexual innuendoes without disgruntling anyone in power.3 She wrote not in the language of her birth, but in the language of the country she made home.

2 ] One of the first women known to have earned a living through writing, Christine de Pizan was brought to France as a child after her father, a professor at the University of Bologna, entered the court of Charles V as a physician and astrologer. In 1390, Christine's husband died suddenly, leaving her with three children to support, along with a niece and widowed mother. Christine began writing, undertaking a rigorous course of independent study, securing royal patrons, and producing an astonishing body of work in a brief span of approximately 20 years.

For her early lyric poetry, Christine took as her model the poetic formes fixes outlined by Eustache Deschamps in his Art de dictier (The Art of Writing Poetry), a leading authority of the era, along with Guillaume de Machaut, who pioneered the French poetic vernacular.4 At the same time, Christine re-imagined conventional courtly themes—previously engaged with idealized notions of chivalric love—to convey the deeps bonds of a happy marriage and the piercing loss of widowhood.

3 ] In a letter dated February 10, 1404, Christine wrote to Deschamps, twenty years her senior: "Your great reputation has encouraged me, dear master and friend, to send you this. . . . if you would like to see examples of my little understanding in my works, you can order them, without special inquiries for I'm looking for your comments." Deschamps responded with generosity and kind encouragement, likening Christine to one of the nine muses and thanking her "a hundred times" for her letter, "received with great joy."

Their exchange, translated into English by Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski,5 reminds me of Emily Dickinson's letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, written over four hundred years later in another language, another country: "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive? The mind is so near itself it cannot see distinctly, and I have none to ask."

Both women, extraordinary in their work, felt alone in their undertaking. And they were. Both wrote themselves into a literary world inhabited by men, and in doing so, expanded that world for others through the newness and possibility of their language.

4 ] Christine often referred to herself as seulette, a woman alone, small and of little consequence in comparison to the male auctours of her time. In a time and place unaccustomed—even hostile—to independent women, Christine undertook to produce manuscripts for royals. That her books are read and studied centuries after their making is its own small miracle. In part, it was achieved through Christine's own brilliance and fortitude. In part, it was the support of those in power who helped her—and the translators who continue to bring her writing into language anew.6

5 ] One day, fortune brought me into the gracious presence of one of those translators, a preeminent scholar of medieval French and Italian literature who answered my most basic of questions as if they were the most critical he had ever heard.

Q. Do you think Christine spoke Italian at home with her mother?

A. Well, hmmm. We can't know for certain, but yes, yes. I imagine she did.

Q. Do you think Christine ever wanted to marry again?

A. Well now, let me think about that some more.

6 ] In learning her craft as a poet, Christine practiced the formes fixes of the ballade and the rondeau. Both make appearances in « widow rounds », with the Middle French versions found in the first volume of Oeuvres poétiques de Christine de Pisan, edited by Maurice Roy and published in 1886.

When I first searched for the Roy volumes, they were missing from the library shelves. But they found me soon enough, as did the codex of a queen.

7 ] Translation, or "translacion" as she calls it, is not a neutral subject for Christine. She will never write in Italian, but her native language exists within her like a source or a potential resource.7

8 ] In learning how to translate Christine, I first looked to the translators and scholars who brought her to me. I looked to dictionaries and chronicles. I glossed, erased, and invented.8 But the poems themselves were conveyed by language that had taken up residence within me, though I had yet to know it.

9 ] In 1418, civil violence and foreign invasion caused Christine to flee Paris. She is believed to have spent the last dozen years of her life in an enclosed abbey, a kind of exile-by-circumstance. With the exception of two manuscripts (one of which is the first poem relaying Joan of Arc's 1429 victory at Orléans), no writing from these years are known to exist, but the more I learned about Christine, the more I began to wonder.

Amid the cadence of wondering, the language dwelling inside emerged as Marina's, a young woman of imagining who serves as scribe for Christine during this historical period of silence.

10 ] Poetry comes to know that things are. But this is not knowledge in the strictest sense; it is, rather, acknowledgment––and that constitutes a sort of unknowing.9

When I first saw Christine's name, French was not a language I knew well. I am learning it still. Marina made translation possible. She refused silence to what is unknown.10 Whether she translated me or I translated her, I cannot say.

11 ] The work of translation might thus be said to carry a double duty: to expropriate oneself as one appropriates the other. We are called to make our language put on the stranger's clothes at the same time as we invite the stranger to step into the fabric of our own speech.11

12 ] The ballade and rondeau of Christine's poetic apprenticeship emerged out of dance and song traditions; as portrayed in The Queen’s Manuscript of 1414, their lyrical music depended not on punctuation cues, but on an understood knowledge of the forms. The question then became: How might I convey this music to the unfamiliar while carrying over a sense of the manuscript original? Maybe more urgently: How might the voice of the woman who composed these poems resonate six hundred years after the keen grief that compelled their making?

To know that things are is not to know what they are, and to know that without what is to know otherness (i.e., the unknown and perhaps unknowable).12

Some say all poetry is translation. Whether this can be known, I cannot say, only that Marina's invention permitted me to enter the music of Christine's voice more deeply, in what Earl Jeffrey Richards recalls as the here and now. What remains constant: To hear a voice that sings across time and space is to understand our own experience as knit to others. Maybe this is one way translation expands the possibility for knowing, the capacity for compassion.

Q. And the woman who called herself seulette?

A. Yes, now that you ask. Yes, I think she married poetry.

Inside the presence of each other's language, we are never alone.

────────────

Christine de Pizan. The Queen's Manuscript. Hosted online by the British Library as Harley MS 4331. Further information available through the collaborative digital project, The Making of the Queen's Manuscript.

Œuvres poétiques de Christine de Pisan. Ed. Maurice Roy. 3 vols. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot et Cie: 1884-96. Accessed online through Gallica, the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Cerquiglini, Jacqueline. "The Stranger." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Cotgrave, Randle, A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues, London: Adam Islip, 1611. Accessed online from facsimile scans made in the French National Library by Greg Lindahl.

Hejinian, Lyn. The Language of Inquiry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Margolis, Nadia. An Introduction to Christine de Pizan. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Richards, E. Jeffrey, ed. Christine de Pizan and Medieval French Lyric. Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 1998.

Ricoeur, Paul. On Translation. Trans. Eileen Brennan. Intro. Richard Kearney. London & New York: Routledge, 2006.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. "The Politics of Translation." Outside in the Teaching Machine. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Marci Vogel is the author of At the Border of Wilshire & Nobody. Her poetry, essays, and translations appear in Jacket2, Plume, Waxwing, Brooklyn Rail, and The Account, among others. The recipient of a Willis Barnstone Translation Prize and Hillary Gravendyk Memorial Scholarship, she is currently a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at the University of Southern California.

This originally appeared on July 14, 2017